NEW ZEALAND'S TOUGHEST ENDURO?

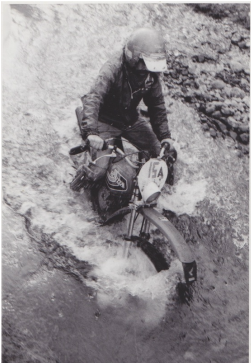

Here I am on the XL250S in the Waipakeke Stream.

Looking back to the 1978 Hikutaia Enduro it seems scarcely possible that it really happened. In a competition career that spanned from 1969 to 1992 I came up against some challenges, but this one day enduro was by far the most challenging event I ever rode.

Kiwi enduro riders are used to doing it tough - our terrain is notoriously steep and wet. In parts on NZ it is almost impossible to map out and easy event. In the 1970s when the ethos was for tough events, the clue was right there in the sport's very name, enduro. Riders were expected to endure and they did just that, the attitude was one of never say die, to finish was everything. Shunning showy special tests, enduros of the day were in effect battles against the terrain and exhaustion, not seconds counted on the clock. Yes times were set for sections, but cumilatively it was expected to be virtually impossible to stay on-time, even the winner should lose a good fist of minutes - a scenario not unlike today’s Extreme Enduros.

The chief architects of the 1978 Hikutaia Enduro, John Isdaile and Lester Yates were legendary hard-men born and bred in the Coromandel Ranges and for them steep, slippery, and wet, are all relative terms. The course was a massive piece of work, typical of national Enduros of the day, one giant loop of terrain with off road sections linked by road stages on public roads. The entire loop to be ridden only once and would take six to eight hours - all going well. Included in this plot were two complete crossings of the ranges, plus daunting obstacles; horrendously steep climbs, slimy soapstone rock, countless creek crossings, dripping rainforest, tangles of vines, gardens of tree roots, festering swamps and endless crankcase deep ruts. The total effect, compounded by copious rain, was a grovel of titanic proportions.

Kiwi enduro riders are used to doing it tough - our terrain is notoriously steep and wet. In parts on NZ it is almost impossible to map out and easy event. In the 1970s when the ethos was for tough events, the clue was right there in the sport's very name, enduro. Riders were expected to endure and they did just that, the attitude was one of never say die, to finish was everything. Shunning showy special tests, enduros of the day were in effect battles against the terrain and exhaustion, not seconds counted on the clock. Yes times were set for sections, but cumilatively it was expected to be virtually impossible to stay on-time, even the winner should lose a good fist of minutes - a scenario not unlike today’s Extreme Enduros.

The chief architects of the 1978 Hikutaia Enduro, John Isdaile and Lester Yates were legendary hard-men born and bred in the Coromandel Ranges and for them steep, slippery, and wet, are all relative terms. The course was a massive piece of work, typical of national Enduros of the day, one giant loop of terrain with off road sections linked by road stages on public roads. The entire loop to be ridden only once and would take six to eight hours - all going well. Included in this plot were two complete crossings of the ranges, plus daunting obstacles; horrendously steep climbs, slimy soapstone rock, countless creek crossings, dripping rainforest, tangles of vines, gardens of tree roots, festering swamps and endless crankcase deep ruts. The total effect, compounded by copious rain, was a grovel of titanic proportions.

an innocuous start...........

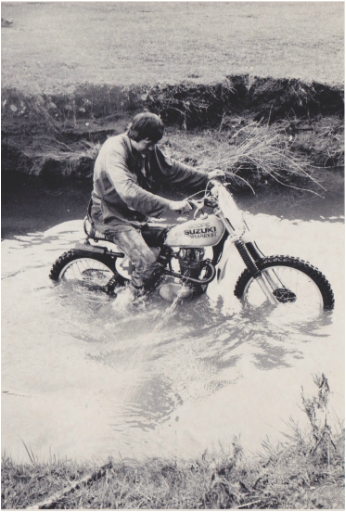

Tjebbe Bruin cooling down in the stream at Hikuatia.

This day in 1978 started with a fairly innocuous 20km mixed farmland and bush section that included a run up a creek bed with plenty of crossings, followed by some slippery steep farmland. All up, an interesting but unremarkable start to a day’s riding that was soon to become anything but unremarkable.

Previous Hikutaia Enduros had included a run down a notoriously steep track, on maps called the Waipaheke, but known by riders as the Gut Buster. However, only a short distance into section two, it began to dawn on me that the arrows were not taking us on our usual route via the 4x4 track to the top of the ranges. Almost incredibly we were heading into the valley of the Waipakeke, meaning only one thing, the unthinkable… we were going UP the Gut Buster.

My brain was recoiling. How were eighty riders going to struggle up a rocky, slippery, clay single-track that climbs over 1000 metres in barely three kilometres, and how, as rider number 20, well back in the field, would I pass the up to 60 riders ahead of me if there was a bottleneck? All I could think of as a strategy was to pass as many riders as possible before the steep part of the climb. I had two, perhaps three kilometres before things would get really ugly. What other riders thought of me I have no idea, but by bouncing off banks and jumping into creeks I was able to pass riders in ones and twos. My looney charge was at least moving me up the ranks.

Overnight rain had left the surface slippery and the first real bottleneck was an ugly sight - a heaving mass of riders, screaming engines and tortured rubber, dimly seen through a choking fog of 20:1 pre-mix. With vital National Championship points at stake I could only make progress by launching forward, but how to achieve traction when all around tyres spun hopelessly? Inspiration lit up in my adrenalin-filled brain. Tyre pressure, damn the rocks, let it all out, every last bit.

By this time riders around me were taking off helmets, reaching for chocolate bars and making eye contact with strong looking fellows who might make good pushing mates. While that was the best option of last resort, I was not yet ready to yield. I could see riders further ahead still making progress unaided - there was still hope.

Backing up into some bushes with my flat-to-the-rim rear tyre I sighted up the best line I could see and hooked second gear. Yelling lustily to warn those in my path that I was attempting to come through I wound the XL250 up to valve float, dumped the clutch and hung on.

Luck was with me, my flat rear tyre found some grip and with a few good souls leaning their bikes to the side and another fortuitously falling out of the way down a bank, I was underway and kept the charge going. With aching arms and pumping legs I managed to keep the Honda front wheel pointed upwards, zig-zagging from one side of the track to the other, around stalled bikes and collapsed riders. After each pinch, there were fewer victims and less smoke. Now the trail was opening out, enough for second gear in places. But before I could think about making up for lost time I had use my trusty tyre pump to get some air in the rear tyre. Luck was with me again, I had not pinched the tube on the rocks and the pressure held.

At Iast I could get into the rhythm of riding the rest of the section over the ranges towards the next checkpoint, before the drop into the Wentworth Valley. At the check I was annoyed to see I was seven minutes late, yet surprised when they slapped me on the back and announced that I was the third rider to arrive. Amazing how fast disappointment can turn to elation, but you might already have guessed there was plenty of ego-levelling drama to come.

Previous Hikutaia Enduros had included a run down a notoriously steep track, on maps called the Waipaheke, but known by riders as the Gut Buster. However, only a short distance into section two, it began to dawn on me that the arrows were not taking us on our usual route via the 4x4 track to the top of the ranges. Almost incredibly we were heading into the valley of the Waipakeke, meaning only one thing, the unthinkable… we were going UP the Gut Buster.

My brain was recoiling. How were eighty riders going to struggle up a rocky, slippery, clay single-track that climbs over 1000 metres in barely three kilometres, and how, as rider number 20, well back in the field, would I pass the up to 60 riders ahead of me if there was a bottleneck? All I could think of as a strategy was to pass as many riders as possible before the steep part of the climb. I had two, perhaps three kilometres before things would get really ugly. What other riders thought of me I have no idea, but by bouncing off banks and jumping into creeks I was able to pass riders in ones and twos. My looney charge was at least moving me up the ranks.

Overnight rain had left the surface slippery and the first real bottleneck was an ugly sight - a heaving mass of riders, screaming engines and tortured rubber, dimly seen through a choking fog of 20:1 pre-mix. With vital National Championship points at stake I could only make progress by launching forward, but how to achieve traction when all around tyres spun hopelessly? Inspiration lit up in my adrenalin-filled brain. Tyre pressure, damn the rocks, let it all out, every last bit.

By this time riders around me were taking off helmets, reaching for chocolate bars and making eye contact with strong looking fellows who might make good pushing mates. While that was the best option of last resort, I was not yet ready to yield. I could see riders further ahead still making progress unaided - there was still hope.

Backing up into some bushes with my flat-to-the-rim rear tyre I sighted up the best line I could see and hooked second gear. Yelling lustily to warn those in my path that I was attempting to come through I wound the XL250 up to valve float, dumped the clutch and hung on.

Luck was with me, my flat rear tyre found some grip and with a few good souls leaning their bikes to the side and another fortuitously falling out of the way down a bank, I was underway and kept the charge going. With aching arms and pumping legs I managed to keep the Honda front wheel pointed upwards, zig-zagging from one side of the track to the other, around stalled bikes and collapsed riders. After each pinch, there were fewer victims and less smoke. Now the trail was opening out, enough for second gear in places. But before I could think about making up for lost time I had use my trusty tyre pump to get some air in the rear tyre. Luck was with me again, I had not pinched the tube on the rocks and the pressure held.

At Iast I could get into the rhythm of riding the rest of the section over the ranges towards the next checkpoint, before the drop into the Wentworth Valley. At the check I was annoyed to see I was seven minutes late, yet surprised when they slapped me on the back and announced that I was the third rider to arrive. Amazing how fast disappointment can turn to elation, but you might already have guessed there was plenty of ego-levelling drama to come.

and then it got hard..............

The late Sideways Sid Bailey, sans helmet peak, leading a group of riders at the VSE on his Honda trials bike.

Midway through section five I was climbing back into the ranges again behind the town of Whangamata when I sensed disaster. I could smell engine oil and having had problems earlier in the season with the countershaft oil seals blowing and pumping all the engine oil from the crankcase, I looked down with dread at the seal. The seal was intact but almost as bad, I could see the last dribbles of my sump oil coming from the sump plug hole, on the XL250S positioned on the lower left side of the crankcase.

For a few minutes I sat there stunned unable to accept that after all that effort the sump plug was gone, the oil was gone and my day, possibly the entire season was stuffed. Then it dawned on me, the hole could be plugged and if I could find some oil all might not lost. I sat up and looked around, the silence was almost absolute, there were no riders near me yet. In three directions all I could see were hundreds of thousands of acres of pine trees and native bush, but to the south of the track, quite close, was steep hill country farmland and in a little valley a windy track led down to an old woolshed. Parked by the woolshed was a 4x4 and I could just hear a dog barking. Heck, it was worth a try.

Bush bashing for a couple of hundred metres I came out on the grassland and in another few minutes reached the shed. The bloke and his dog looked remarkably unsurprised to see a sweating enduro rider clomp into his the shed. “Yeah,” he said when I explained my predicament, “I heard a some bikes riding down the valley towards Whangamata, but they are pretty spread out.”

“Have you got any oil you can sell me?” I asked hopefully. “Not much here up at this shed,” he said, “but I can give you some shearing handpiece oil from that tin, will that do?” Within a couple of minutes I was on my way back, puffing up the hill and through the bush clutching an ancient glass milk bottle of whatever oil was used in shearing handpieces.

Now riders were coming past in ones and twos. “You OK?” they would shout? “Yeah, I’ll be going again in a minute.” My plan was to bung the sump hole with a piece of stick whittled from a bush, but I found that my spare spark plug was a sort-of fit. Within minutes I was off, the engine performing and sounding great on sheep oil.

But the enduro didn’t get any easier. Section six in the Whangamata Forest offered more hills. One of these featured shiny, white, hard clay, so steep and so slippery I could not stand upright, but had to move about on all fours to retrieve my bike when we parted company. Again my solution to was to let every last puff of air from the rear tyre and rely on the rim lock to keep the tyre on the rim. At this hill, (called to this day simply, “The White Hill Climb”) I teamed up with my mate TJ Bruin. TJ had been held up on the Waipaheke when his XL 250 special lost sparks while making good prgress up the climb. TJ was amazed to find that the XL had got so hot that the insulation had melted from the wire to the ignition points and they had shorted out, requiring a quick trailside re-wire. It was obvious that if there was any more of this kind of fun, only mutual support would win through.

Now the event was swinging west again from Tairua towards our next crossing of the Coromandel Ranges and if conditions were not hard enough it started raining. We had made up some time, passing a few riders, but we all were very thin on the ground now and it was awfully lonely out there, no houses or settlements in sight, just cold, dripping rainforest and mountains.

It was in the Neavesville Bush, section eight that the enduro got really hard. Arrows directed us off a rough enough 4x4 track into what appeared solid jungle. You must be joking, I thought, someone has turned an arrow around. But sure enough further in the bush were a second and third arrow, and slowly it dawned that there was in fact a faint overgrown miner’s pack track, disappearing into the overgrown gloom. Now we were up against deep ruts, through glutinous mud, interlaced with fiendish tree roots. All we could do was keep moving forward, sometimes surging forward up 10 metres in first gear, but more often just a metre or two before a root would snare a footpeg or an entire wheel, and we would have to team up again and manhandle the bikes one at a time.

By now humour and fitness had leached away, this was a struggle to the finish, made even more compelling by the remoteness of our situation. Most of the riders we encountered were forming little groups, we were not racing in the conventional sense, and it was obvious that once into this section the only way to avoid a freezing night in the bush would be to push on.

And we did, somehow. It’s sort of hazy now, it was even then, but I still remember the point where even as a man who admires a challenge, I felt this ride might loose it's appeal. At one point the track crew had erected a sign labelled “Parachute Drop”. The sign was an excuse to stop, I actually thought it was intended as a joke, but no, the route now left the ridge and plunged forty degrees down into a side valley through apparently virgin bush. Bulldogging was the only way down but several times I lost my footing and simply had to let the bike plunge away downwards until the footpeg or handlebar dug in, or caught on a tree. At one point the front wheel snagged on a tree and the XL was supended on the slope, the tree wedged up between the tyre and the mudguard. The only way to free it was to haul the back of the bike up higher than the tree. It took two of us to do so and when we did the Honda simply slid away from us again, crashing down through the vegetation to hang up again in the same way further down.

On we went, up more hills, through more creeks, would this ride ever end? By now I had lost all sense of timing, I hadn't even bothered to zero my watch or speedo for hours, it was simply a matter of plugging on.

Our finish, just on dark after around eight hours riding was a blessed relief. We handed in our cards to be told we had probably managed third and sixth in class. Climbing into clean, warm, dry clothes we soon began to feel the glow of a hard job done.

Remarkably the man who won the 1978 Hikataia Enduro was Sideways Sid Bailey riding a Honda TL250 trials bike. Sideways had used his trails skills and his trials bike's inherent advantages in super- tough going to forge on way ahead of all the field in what must have been a very lonely ride. Sid is sadly no longer with us but his effort in winning that Enduro remains legend.

The following day TJ and I sat on the porch in the sun savouring endless cups of tea, moving like ancient men. It had been an almighty day of effort, nothing I have done before or since, comes close, but then little else has given me more satisfaction than finishing the 1978 Hikutaia Enduro.

Click this link to the results of the 1978 Hiutaia Enduro.

For a few minutes I sat there stunned unable to accept that after all that effort the sump plug was gone, the oil was gone and my day, possibly the entire season was stuffed. Then it dawned on me, the hole could be plugged and if I could find some oil all might not lost. I sat up and looked around, the silence was almost absolute, there were no riders near me yet. In three directions all I could see were hundreds of thousands of acres of pine trees and native bush, but to the south of the track, quite close, was steep hill country farmland and in a little valley a windy track led down to an old woolshed. Parked by the woolshed was a 4x4 and I could just hear a dog barking. Heck, it was worth a try.

Bush bashing for a couple of hundred metres I came out on the grassland and in another few minutes reached the shed. The bloke and his dog looked remarkably unsurprised to see a sweating enduro rider clomp into his the shed. “Yeah,” he said when I explained my predicament, “I heard a some bikes riding down the valley towards Whangamata, but they are pretty spread out.”

“Have you got any oil you can sell me?” I asked hopefully. “Not much here up at this shed,” he said, “but I can give you some shearing handpiece oil from that tin, will that do?” Within a couple of minutes I was on my way back, puffing up the hill and through the bush clutching an ancient glass milk bottle of whatever oil was used in shearing handpieces.

Now riders were coming past in ones and twos. “You OK?” they would shout? “Yeah, I’ll be going again in a minute.” My plan was to bung the sump hole with a piece of stick whittled from a bush, but I found that my spare spark plug was a sort-of fit. Within minutes I was off, the engine performing and sounding great on sheep oil.

But the enduro didn’t get any easier. Section six in the Whangamata Forest offered more hills. One of these featured shiny, white, hard clay, so steep and so slippery I could not stand upright, but had to move about on all fours to retrieve my bike when we parted company. Again my solution to was to let every last puff of air from the rear tyre and rely on the rim lock to keep the tyre on the rim. At this hill, (called to this day simply, “The White Hill Climb”) I teamed up with my mate TJ Bruin. TJ had been held up on the Waipaheke when his XL 250 special lost sparks while making good prgress up the climb. TJ was amazed to find that the XL had got so hot that the insulation had melted from the wire to the ignition points and they had shorted out, requiring a quick trailside re-wire. It was obvious that if there was any more of this kind of fun, only mutual support would win through.

Now the event was swinging west again from Tairua towards our next crossing of the Coromandel Ranges and if conditions were not hard enough it started raining. We had made up some time, passing a few riders, but we all were very thin on the ground now and it was awfully lonely out there, no houses or settlements in sight, just cold, dripping rainforest and mountains.

It was in the Neavesville Bush, section eight that the enduro got really hard. Arrows directed us off a rough enough 4x4 track into what appeared solid jungle. You must be joking, I thought, someone has turned an arrow around. But sure enough further in the bush were a second and third arrow, and slowly it dawned that there was in fact a faint overgrown miner’s pack track, disappearing into the overgrown gloom. Now we were up against deep ruts, through glutinous mud, interlaced with fiendish tree roots. All we could do was keep moving forward, sometimes surging forward up 10 metres in first gear, but more often just a metre or two before a root would snare a footpeg or an entire wheel, and we would have to team up again and manhandle the bikes one at a time.

By now humour and fitness had leached away, this was a struggle to the finish, made even more compelling by the remoteness of our situation. Most of the riders we encountered were forming little groups, we were not racing in the conventional sense, and it was obvious that once into this section the only way to avoid a freezing night in the bush would be to push on.

And we did, somehow. It’s sort of hazy now, it was even then, but I still remember the point where even as a man who admires a challenge, I felt this ride might loose it's appeal. At one point the track crew had erected a sign labelled “Parachute Drop”. The sign was an excuse to stop, I actually thought it was intended as a joke, but no, the route now left the ridge and plunged forty degrees down into a side valley through apparently virgin bush. Bulldogging was the only way down but several times I lost my footing and simply had to let the bike plunge away downwards until the footpeg or handlebar dug in, or caught on a tree. At one point the front wheel snagged on a tree and the XL was supended on the slope, the tree wedged up between the tyre and the mudguard. The only way to free it was to haul the back of the bike up higher than the tree. It took two of us to do so and when we did the Honda simply slid away from us again, crashing down through the vegetation to hang up again in the same way further down.

On we went, up more hills, through more creeks, would this ride ever end? By now I had lost all sense of timing, I hadn't even bothered to zero my watch or speedo for hours, it was simply a matter of plugging on.

Our finish, just on dark after around eight hours riding was a blessed relief. We handed in our cards to be told we had probably managed third and sixth in class. Climbing into clean, warm, dry clothes we soon began to feel the glow of a hard job done.

Remarkably the man who won the 1978 Hikataia Enduro was Sideways Sid Bailey riding a Honda TL250 trials bike. Sideways had used his trails skills and his trials bike's inherent advantages in super- tough going to forge on way ahead of all the field in what must have been a very lonely ride. Sid is sadly no longer with us but his effort in winning that Enduro remains legend.

The following day TJ and I sat on the porch in the sun savouring endless cups of tea, moving like ancient men. It had been an almighty day of effort, nothing I have done before or since, comes close, but then little else has given me more satisfaction than finishing the 1978 Hikutaia Enduro.

Click this link to the results of the 1978 Hiutaia Enduro.