A TRAIN SPOTTER'S GUIDE

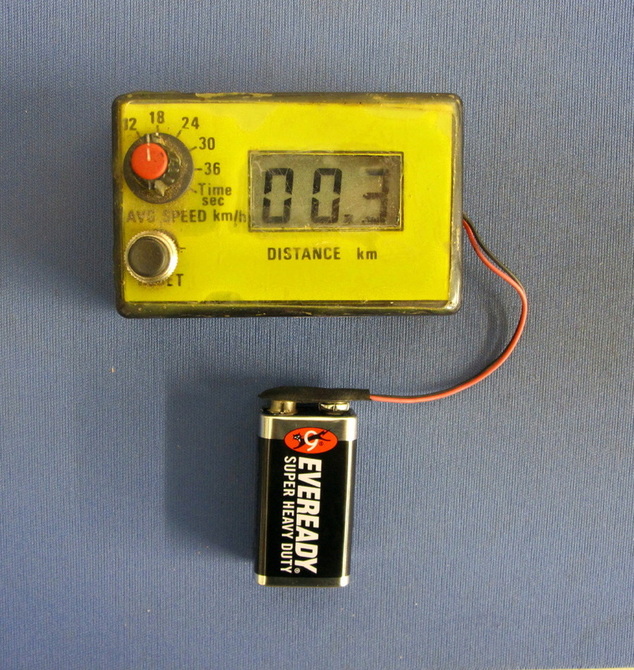

Mark Macdonald's NZ designed and built enduro computer from the 1980s. Though the FIM rules were in place by this time Mark (then NZ Champion) had learned to ride to time and still liked to know how hard he had to push to ensure he would not be late. This simple device was fitted alongside the odometer. The rider set the dial to the section average speed and hit the zero button when the section started. All that you then had to do was make sure your odometer reading did not fall behind the distance displayed on the computer. And amazingly after 25 years it still works!

New Zealand Enduros were modeled on USA style events. These rules are somewhat different in concept and scoring to the current semi-FIM style now broadly used in modern NZ Enduros. The USA system was used in NZ up until about 1978 and this helped form the unique character of the 1970s events.

The USA enduro scoring system (sometimes called the New England Interval system) allows for a course to be set with public road sections within the course to join the off road bits. An average speed is set that allows riders to easily come in on time on the road sections, but is very hard (or more likely impossible) to achieve on the tighter off road stretches. To achieve the event comprises a mix of checks where the distance to the check is either known or unknown. All the rider knows is what average speed they need to do to get in on time. As the rider can loose points for both early and late arrival at secret checks, the effect is that you end up riding conservatively on roads (and easy off road sections) and flat out whenever the terrain gets difficult. By careful selection of checkpoint placement and average speed required, the organiser can catch out anyone who speeds on a road section (say through town) and still find out who is the best rider in tough off road going.

The NEI system though seemingly more intellectual is also simpler in other ways to ride and organise as the system of flip cards effectively digitises time so that the number shown on the cards at the check is the rider's due time. In FIM events riders are scored in real time including hours and minutes.

PROS AND CONS

• The organiser can mark out a big single lap loop of terrain using several different types of, and often widely spread, off road riding areas. Enduros used to cover big areas of terrain within a region and it was possible to start and run riders right through the centre of towns, even a city. Obviously the machines were then all road legal.

• Because riders had to ride conservatively on easy ground and were only penalised in tough terrain, the course was generally safer to riders. For the same reasons slower riders were less likely to fall far behind time as they could easily achive the required average on the easy terrain, that made up about two thirds of an average ride.

• Scoring is very quick and easy to calculate as the event finishes as the rider's entire score is on the rider's card and there are no special test scores to calculate and then incorporate.

• The main difficulty of the USA system was getting your head around how it worked, as an organiser or as a rider. Most organisers could get it, but the same can't be said for riders. For those riders who wanted a simple all-day throttle to the stop experience the need to ride conservatively on easy terrain and flat out in tough going was hard to swallow.

HOW IT WORKED

To allow riders to more easily ride to time average speeds are all set in multiples of 6 kph, being easily divisible into 60 minutes. Therefore a 6kph average speed requires that you cover 0.1 of a km every minute and 30kph, 0.5 of a km, and so on.

The USA scoring system allows for no special tests and bonus points, the result is achieved solely by time lost, mostly in tough sections and any time you were silly enough to loose by arriving early on the road, or in easy terrain. The rider with the lowest score was the winner. To break possible ties one section of tough terrain was timed to the second, the object being to arrive closest to the middle of your minute due. An optional tie breaker was a short speed test of up to a minute. In practice very few events required the tie breaker to be used. (Raglan Enduro in 1977 was one example, where Blair Harrison won by just one tenth of a second on the tie break).

To keep to time riders would mount a watch to one side of the speedo to compare distance covered and time elapsed. More serious riders invented ways to made the calculation even easier, such as the home-made pocket watch caclulator. This device allowed a ring with the correct distances marked on it to be clipped over the (analogue, pre-digital!) watch. Once the right ring for the average required was clipped in place the minute hand of the watch automatically displayed the distance you should have covered. Later, when the USA system was almost out of use in NZ, then NZ Enduro Champ Mark Macdonald built and sold an electronic computer that worked very well.

THE CHANGE TO FIM

By 1978 the USA system was falling out of favour in NZ. To some it seemed rooted in the tough events of the 70s, a style of event that some in the fraternity and motorcycle industry were vocally calling for the end of. At the same time more riders were interested in traveling to Australia and Europe to ride pure FIM events like the ISDE where MX special test skills were paramount. At the end of the 1978 season a directive was given to organisers to make Enduros easier and a simplified hybrid form of FIM rules with special tests and bonus points were implemented. Elements of the USA system are still however seen in NZ today, such as the flip cards that give the riders a simple number to ride to, rather than the FIM's real time hour and minute system. Another hangover are 6kph average speed multiples for sections. Of course just directing a culture to change doesn't make it do so, at least not quickly and NZ Enduro oganisers (with the help of rain and terrain) continued to throw up challenging rides with tough, tight, sections that simply could not be 'zeroed'. Big loop events were still being run with road sections and diverse terrain up into the late 90s but the dropping of road legal requirements consigned Enduros into the single dimension multi loop format we now see.

WAS IT GOOD?

In my view (though I bowed to pressure and helped usher in the change to multi-lap FIM special test dominated events) I believe the USA system, has definite advantages, especially when used in events that include on and off road terrain. Certainly it allows the organiser more flexibility in setting out a ride and encourages more varied single lap loop off road terrain. At the same time I feel it draws a clearer distinction between Enduro and MX/Cross Country.

The USA system is still used in that vast country with more enduro riders than the rest of the world put together. To me the USA system sets Enduro clearly distinct as a competition founded on the ability to ride long distances of very diverse terrain, relying on a balance of determination, technical skill and intellect to win through. Elements of this ethos I believe are now fuelling the increasing interest in Extreme Enduro events.

The USA enduro scoring system (sometimes called the New England Interval system) allows for a course to be set with public road sections within the course to join the off road bits. An average speed is set that allows riders to easily come in on time on the road sections, but is very hard (or more likely impossible) to achieve on the tighter off road stretches. To achieve the event comprises a mix of checks where the distance to the check is either known or unknown. All the rider knows is what average speed they need to do to get in on time. As the rider can loose points for both early and late arrival at secret checks, the effect is that you end up riding conservatively on roads (and easy off road sections) and flat out whenever the terrain gets difficult. By careful selection of checkpoint placement and average speed required, the organiser can catch out anyone who speeds on a road section (say through town) and still find out who is the best rider in tough off road going.

The NEI system though seemingly more intellectual is also simpler in other ways to ride and organise as the system of flip cards effectively digitises time so that the number shown on the cards at the check is the rider's due time. In FIM events riders are scored in real time including hours and minutes.

PROS AND CONS

• The organiser can mark out a big single lap loop of terrain using several different types of, and often widely spread, off road riding areas. Enduros used to cover big areas of terrain within a region and it was possible to start and run riders right through the centre of towns, even a city. Obviously the machines were then all road legal.

• Because riders had to ride conservatively on easy ground and were only penalised in tough terrain, the course was generally safer to riders. For the same reasons slower riders were less likely to fall far behind time as they could easily achive the required average on the easy terrain, that made up about two thirds of an average ride.

• Scoring is very quick and easy to calculate as the event finishes as the rider's entire score is on the rider's card and there are no special test scores to calculate and then incorporate.

• The main difficulty of the USA system was getting your head around how it worked, as an organiser or as a rider. Most organisers could get it, but the same can't be said for riders. For those riders who wanted a simple all-day throttle to the stop experience the need to ride conservatively on easy terrain and flat out in tough going was hard to swallow.

HOW IT WORKED

To allow riders to more easily ride to time average speeds are all set in multiples of 6 kph, being easily divisible into 60 minutes. Therefore a 6kph average speed requires that you cover 0.1 of a km every minute and 30kph, 0.5 of a km, and so on.

The USA scoring system allows for no special tests and bonus points, the result is achieved solely by time lost, mostly in tough sections and any time you were silly enough to loose by arriving early on the road, or in easy terrain. The rider with the lowest score was the winner. To break possible ties one section of tough terrain was timed to the second, the object being to arrive closest to the middle of your minute due. An optional tie breaker was a short speed test of up to a minute. In practice very few events required the tie breaker to be used. (Raglan Enduro in 1977 was one example, where Blair Harrison won by just one tenth of a second on the tie break).

To keep to time riders would mount a watch to one side of the speedo to compare distance covered and time elapsed. More serious riders invented ways to made the calculation even easier, such as the home-made pocket watch caclulator. This device allowed a ring with the correct distances marked on it to be clipped over the (analogue, pre-digital!) watch. Once the right ring for the average required was clipped in place the minute hand of the watch automatically displayed the distance you should have covered. Later, when the USA system was almost out of use in NZ, then NZ Enduro Champ Mark Macdonald built and sold an electronic computer that worked very well.

THE CHANGE TO FIM

By 1978 the USA system was falling out of favour in NZ. To some it seemed rooted in the tough events of the 70s, a style of event that some in the fraternity and motorcycle industry were vocally calling for the end of. At the same time more riders were interested in traveling to Australia and Europe to ride pure FIM events like the ISDE where MX special test skills were paramount. At the end of the 1978 season a directive was given to organisers to make Enduros easier and a simplified hybrid form of FIM rules with special tests and bonus points were implemented. Elements of the USA system are still however seen in NZ today, such as the flip cards that give the riders a simple number to ride to, rather than the FIM's real time hour and minute system. Another hangover are 6kph average speed multiples for sections. Of course just directing a culture to change doesn't make it do so, at least not quickly and NZ Enduro oganisers (with the help of rain and terrain) continued to throw up challenging rides with tough, tight, sections that simply could not be 'zeroed'. Big loop events were still being run with road sections and diverse terrain up into the late 90s but the dropping of road legal requirements consigned Enduros into the single dimension multi loop format we now see.

WAS IT GOOD?

In my view (though I bowed to pressure and helped usher in the change to multi-lap FIM special test dominated events) I believe the USA system, has definite advantages, especially when used in events that include on and off road terrain. Certainly it allows the organiser more flexibility in setting out a ride and encourages more varied single lap loop off road terrain. At the same time I feel it draws a clearer distinction between Enduro and MX/Cross Country.

The USA system is still used in that vast country with more enduro riders than the rest of the world put together. To me the USA system sets Enduro clearly distinct as a competition founded on the ability to ride long distances of very diverse terrain, relying on a balance of determination, technical skill and intellect to win through. Elements of this ethos I believe are now fuelling the increasing interest in Extreme Enduro events.